The Magnificent Frigate Bird, known as the man-of-war, pirate bird, and hurricane bird, is a striking presence in the Caribbean sea. It captures prey from the ocean and chases other seabirds, showcasing its strength while soaring high in the sky.

Spanish and Portuguese sailors from centuries ago were amazed when they first saw this impressive creature near the Cape Verde Islands. They named it “rabiforcado,” meaning “forked tail.” Later, 17th century French sailors called it “La frégate,” inspired by the fast ships of their time. Today, these seabirds still manage to impress with their strength.

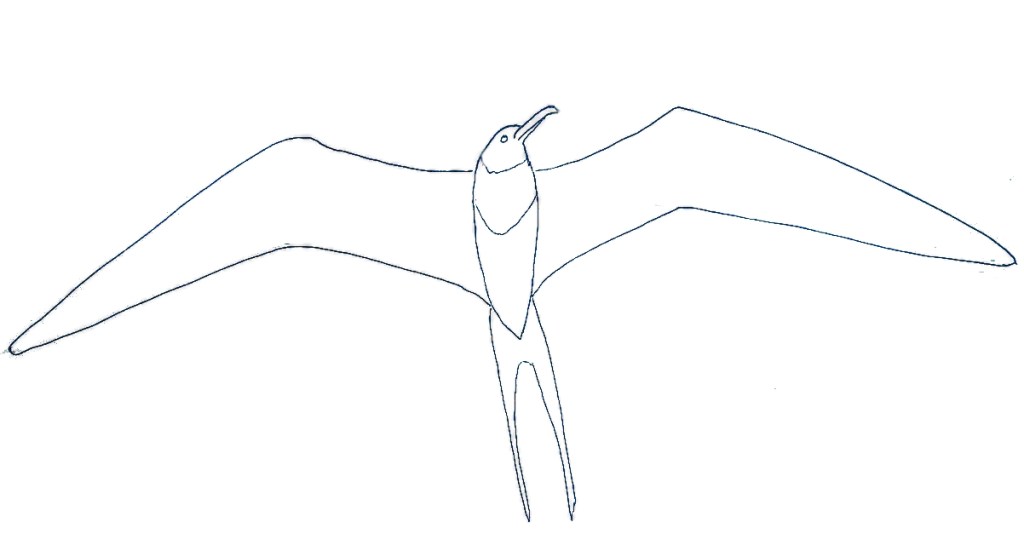

This remarkable bird is perfectly designed for foraging in flight, featuring a lightweight body, strong pectoral muscles, a long tail for agility, and a wingspan over two meters. It has the highest wing surface to body ratio of any bird alive today.

Unlike most seabirds, it has small legs and non-waterproof feathers, which prevent it from landing on the sea. As a result, it remains airborne for weeks, relying on its soaring skills to survive.

The Frigatebird’s ability to fly for such long periods, may explain its two-year commitment to raising its young, the longest parental care period among seabirds. This time is crucial for helping fledglings prepare for the challenges of life on the wing. I was amazed to learn that it takes them nine years to mature and start nesting.

The female of the species takes on the sole responsibility of caring for and feeding the chick when it reaches 11 weeks old, as the male leaves to start molting to attract a new mate. This interesting setup allows males to breed every year, while females breed only every other year.

While preparing for this post, I observed a group of young Magnificent Frigatebirds in St. Georges, Grenada. One bird swooped down to catch a fish from the blue water, effortlessly rising back into the air with impressive acrobatics. The fish wriggled fiercely in an attempt to escape the bird’s hooked bill. For a moment, it seemed to break free, but it was caught again in mid-air and quickly swallowed.

On a different occasion, I was fascinated by the sight of two elegant females with shiny black feathers and clean white chests, smoothly flying at great heights. For 20 minutes, I watched them soar effortlessly, never noticing any movement in their long V-shaped wings.

The males are smaller and have all-black feathers, showcasing a bright red inflatable pouch during the breeding season, which is known as the most extravagant courtship display among seabirds.

Contrary to Christopher Columbus’s claim that Magnificent Frigatebirds “do not leave land twenty leagues,” these birds travel great distances across the ocean to find other colonies for interbreeding.

Recent research highlights the amazing skills of Frigatebirds as they use warm air rising from tradewind clouds in the tradewind and doldrum zones. They soar in circles up to 4,000 meters high and then glide down to hunt near the ocean surface, traveling great distances in this way.

Researchers found that Frigatebirds fly best at altitudes between 50 and 6,000 meters. In these conditions, they use so little energy that their heart rate drops to the level it would be while resting in the nest, enabling them to stay in the air for long periods.

Life on the wing – what is it like?

So, how do these birds sleep and feed always on the wing? Recent studies have confirmed a popular belief: Frigatebirds can sleep while flying. Their sleeping habits are remarkable, as they take quick ten-second naps at night, averaging only 45 minutes of sleep each day.

What’s fascinating is that during power naps, only half of their brain sleeps while the other half stays alert to prevent mid-air collisions.

Feeding in the deep ocean depends on the activities of tuna and dolphins, as these predators drive fish to the surface, allowing birds to swoop down and catch them easily.

Magnificent Frigates live in the tropical Atlantic, the Pacific coast of Central America, and the Galapagos Islands, but they mainly thrive in the Caribbean Sea. They nest in large colonies on remote islands, quiet beaches, and in mangrove swamps.

The largest colony in the region used to be located in Barbuda, where at least 2,500 pairs thrived in Codrington Lagoon National Park. Unfortunately, following Hurricane Irma’s impact in 2017, that number has plummeted to fewer than 500 pairs. Despite this devastation, I remain optimistic, as Frigatebirds are renowned for their resilience against hurricanes. I hope some of these majestic birds have survived and found a safe place again.

In the Caribbean, these birds are in serious trouble. They are threatened by introduced predators, overfishing, and habitat loss from human developments like settlements, marinas, and resorts. Coastal development in the West Indies keeps forcing seabirds away. It’s sad that even though many island nations have conservation laws, they are not properly enforced.

Recent findings show that seabirds are important indicators of ocean health. Their well-being is influenced by chemical and climate changes and disruptions in their food sources. Therefore, seeing seabirds in certain areas can reveal the state of the marine ecosystem, as they are sensitive to environmental changes. Hopefully this understanding will help develop effective conservation plans to protect these unique seabirds and their ocean homes.