LA SAGESSE

Before its destruction, La Sagesse featured a salt pond, a mangrove forest and a peaceful crescent-shaped beach with golden sand and tall palm trees, surrounded by lush vegetation that created a sense of seclusion. Its salt pond and mangrove forest were important bird sanctuaries in the southern Lesser Antilles, particularly for migratory birds. The calm waters and lush mangroves created habitats for diverse wildlife, with the roots of the white and buttonwood mangroves providing safe refuge for about 80 bird species.

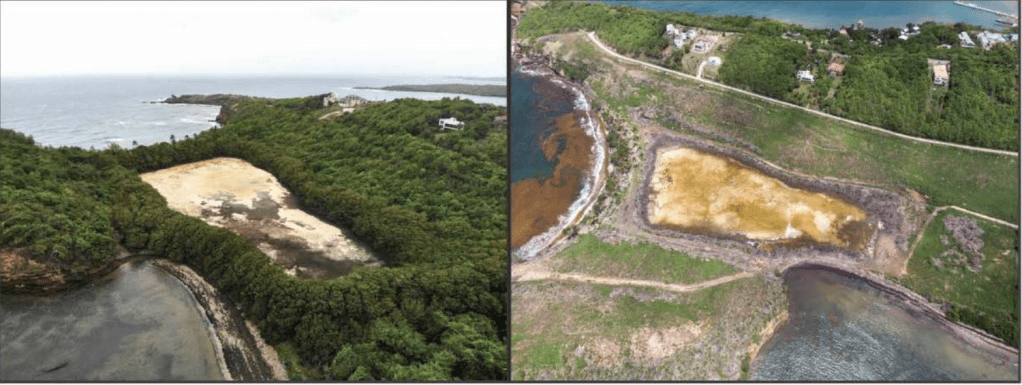

However, in 2019, Range Development Limited cut down the mangrove forest and surrounding plants and dredged the pond to build a large Six Senses hotel complex, which is ironically advertised as a sustainable tourism brand.

This has been one of the most significant ecological crimes on the island, which also deprived the local community of their favourite leisure spot and robbed us of the opportunity to witness many bird species that visited each year.

The Great Blue Heron

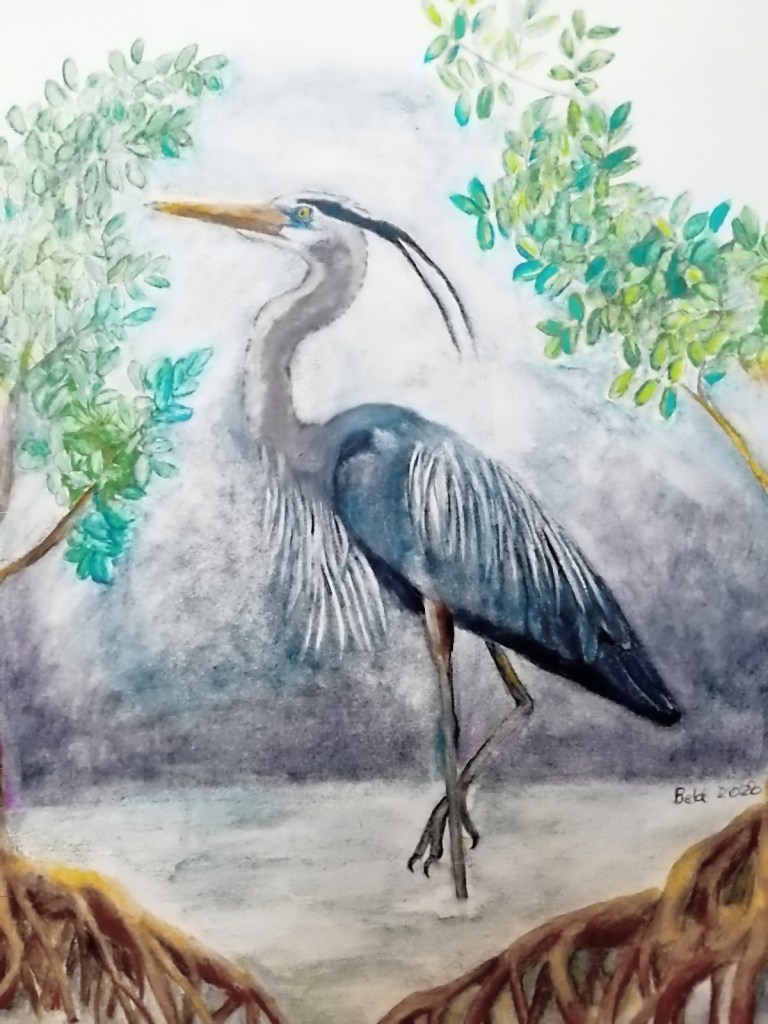

Indeed, it was at La Sagesse Salt Pond that I first saw the Great Blue Heron. Majestic and bright in the morning light, the heron stood picture-perfect, framed by the mangroves at the edge of the pond. Whenever I recall this moment, I now feel a profound sense of loss for something immense that has now been taken away.

Fortunately, a few wetlands remain in Grenada where the Great Blue Heron and other migratory birds can still be seen. Although sightings of Great Blue Herons are rare in the southern Lesser Antilles, I had the opportunity to spot it for the second time in the wetlands of River Antoine, located on the northeast coast. On this occasion, I was equipped with my camera and promptly took a bunch of rather blurry photographs as the heron crossed the muddy riverbank, slowly disappearing into the twilight.

Scientifically known as Ardea herodias, the Great Blue Heron is the largest heron in North America and one of the largest in the world, with a wingspan of six feet (183 cm) and a height ranging from 38 to 54 inches (97-137 cm). Only the sub-Saharan Goliath Heron and the Asian White-Bellied Heron are larger. While Great Blue Herons look similar to Grey Herons, the latter are smaller, lighter in color, and have shorter legs and necks, along with a smaller bill. Adult Great Blue Herons have reddish-brown thighs, while Grey Herons have whitish-grey thighs. Misidentification is rare because these two species do not often share the same habitat. Great Blue Herons are found in North America, Central America, and the Caribbean, while Grey Herons are located in Europe and Asia.

In the Caribbean, Great Blues are common year-round in the Bahamas, Cuba, the Virgin Islands, Aruba, and Bonaire. They have a varied diet and can adapt, which allows them to spend winter months further north than most herons. Each year, around September-October, some migrate from central North America to Trinidad and Tobago and the Northern Coast of South America for the winter.

Great Blue Herons are adaptable birds that can be found along coastlines, beaches, mangrove swamps, rivers, and ponds.

Their impressive foraging skills include fishing and hunting crabs, baby sea turtles, frogs, insects, lizards, snakes, birds, and small rodents.

One of their most notable traits is their excellent night vision, thanks to high-density rod-like cells in their eyes, which help them hunt effectively both day and night.

Great Blue herons are patient hunters, often standing or walking slowly to look for food. Their special neck bones allow them to strike quickly from afar, using their powerful bills to catch prey.

They can hover in the air above the surface, dive feet first to catch prey, and go into deep waters to find food. However, their size makes them vulnerable to capturing prey that is too large to swallow, sometimes resulting in unfortunate outcomes.

Great Blue Herons use impressive displays to firmly secure their foraging areas. Their ‘roh’ calls, arched necks, and circular flights act as warnings to intruders, and the displays become more intense if these warnings are ignored.

The Upright and Spread Wing display, where these birds face each other with their wings open and lowered, is very impressive. As they get closer, their necks stretch out, their heads and bills become more level, and their feathers stand up. This display can also be used against other species, like egrets, gulls, and even people. In rare situations, the heron’s aggression might lead to the dangerous Full Forward Display, where it lunges and may stab its opponent, causing severe injuries or death.

In the Caribbean, Great Blue Herons nest in Cuba, St. John’s in the Virgin Islands, and Los Roques, Venezuela, mainly from December to April. The breeding process starts when males arrive at their chosen site, establishing a display area that serves as the nest, often in a tree fork or an old nest. Males attract females with striking plumes and noticeable Stretch displays, showcasing extended necks, raised neck plumes, upward-pointed bills, gentle swaying, and a soft “cooing” call.

Paired couples strengthen their bond by participating in bill clappering and twig offerings. They collaborate to build the nest, with males collecting sticks and females arranging them into platforms with a bowl shape, lined with soft leaves.

Old nests can be reused and made larger over time, growing up to 1 meter deep and 1.2 meters wide. They are usually built high in trees to avoid ground predators or on remote mangrove islands to stay away from humans.

Females lay 2-7 pale blue eggs, which both birds incubate in 12-hour shifts; males take the day shift and feed at night, while females take the night shift and feed during the day.

After hatching, the grey chicks are watched over by both parents until they are about 28 days old, during which the parents feed them by regurgitating food. The young birds leave the nest at 60 days old and need to learn to avoid predators and hunt for food, but sadly, many do not make it past their first year.

Although Great Blue Herons can live long lives (the oldest recorded in Texas was 24 years and 6 months), most do not reach old age. They are the most common bird predator at US fish hatcheries and are often shot by fish farmers—over 12,000 were legally killed in the southeastern US between 1987 and 1995.

Yet, research shows that the damage done by Great Blues at hatcheries is not always a big issue, as the herons mainly eat sick fish near the surface that are likely to die soon.

But the biggest threat to this species is the harmful effects of farming, which often uses chemicals that pollute the water needed for their survival. Moreover, wetlands are disappearing to create space for tourism, with these important ecosystems being replaced by hotels and resorts.

Known as the “Dinosaur birds,” Great Blue Herons command the attention of both nature enthusiasts and researchers owing to their impressive stature, unique vocalizations, and extraordinary hunting prowess. It would indeed be a grave loss if we were to lose these remarkable modern-day dinosaurs.